Panicked yet determined to elude pursuing law-enforcement officers, the armed-robbery suspect stumbles his way through thick brush in the dead of night. If he can reach the river, he hopes to lose the dogs and any officers on foot.

Surely no police vehicles will be able to get through this morass of tall grass, close-growing scrub oaks, twisting vines, and pine trees. And the airborne cops with their night-vision capabilities haven’t yet had time to scramble a helicopter. He would have heard it by now, and he’ll be long upriver before the helicopter lifts off from the airport helipad.

All the suspect hears is his pounding heart, his gasping for air as he runs nearly full steam through the dark woods toward the perceived safety of the river.

He stops momentarily to catch his breath and get his bearings. The only sound other than his own breathing is the distant roaring of a tractor-trailer heading down the Interstate highway about a mile or so away. That, and frogs. Sounds like millions of them. He must be near the river.

What the fleeing suspect doesn’t hear is, 300 feet off the deck, an unmanned aerial vehicle (UAV or “drone” in popular parlance) with a forward-looking infrared (FLIR) camera mounted under the drone’s nose.

Watching both the dogs and the fleeing felon, the Richland County (South Carolina) Sheriff’s Department DJI Inspire 1 surveillance drone, with its single engine and four small rotors (which is why it’s sometimes referred to as a quadcopter) is as quiet as a perfectly humming weed eater. And that’s what it sounds like.

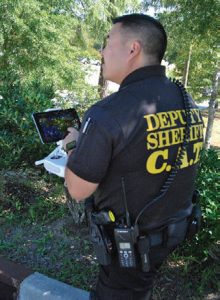

The suspect hasn’t got a chance. His heat signature has already been painted on the remote FLIR screen being monitored by RCSD Master Deputy Marcus Kim, who remotely pilots the department’s three drones. When he’s not flying drones, Kim serves as a member of the department’s Community Action Team, an outreach and community bridging program between the sheriff’s department and the communities it serves.

Table of Contents

FLIR CAMERA

What’s an infrared camera, and what type of FLIR does the Richland County Sheriff’s Department (RCSD) use on its drones? A FLIR camera is essentially a device that produces thermal images on a remote screen by looking at the invisible radiant energy of a source (the heat from a source) as opposed to a conventional camera, which uses existing light.

“This is especially effective at night,” says Deputy Kim. “We can pick up any heat signature from bodies—humans and animals—running cars, even recently driven vehicles when the engine is still hot.”

Part of the RCSD’s “tactical air force,” which also includes two helicopters, the DJI Inspire 1 drone does what the big, expensive, high-maintenance helicopters cannot. Drones are extremely quiet and much more easily deployed.

“If nothing else, drones get on and above the scene quicker,” says Kim.

The RCSD’s drones are relatively small and lightweight—the Inspire 1s in the department’s inventory weigh only about six pounds each—and are transportable in the trunk of a standard police vehicle. They are relatively inexpensive to operate, and not overly pricey on the front end.

The DJI Inspire 1 drone costs about $2,000. But the tiny FLIR camera is not cheap, costing approximately $13,000, whereas the conventional daytime camera costs less than $1,000.

Nevertheless, drones are cost-effective considering their capabilities. And it’s not simply surveillance of fleeing suspects and tracking suspect-pursuing K-9s that make

drones such an effective crime-fighting platform.

Drones are indispensable in 21st-century SWAT operations like those employed by the RCSD’s Special Response Team (SRT), often providing the best—perhaps the only— real-time photographic intelligence for operators on the ground. The drones are also capable of being mounted with an array of weapons if needed. “Everything from tasers to tear-gas to distraction devices, even a small-caliber .380 firearm,” says Kim.

Drones are also especially effective in woodland searches for missing persons.

WHAT’S THE RANGE?

About three miles out and 400 feet off the deck, according to Kim, though for obvious reasons the lateral 360-degree distance and the ceiling limits are rarely if ever tested. An interesting feature of the drone is that if it strays too far, it automatically returns. “The drone sets a GPS home-point when launched,” says Kim. “So if you lose it, it’ll come back to you.”

One of the more interesting recent uses of the RCSD’s drones has been in surveillance of the fenced-perimeters of prisons in Richland County, where

corrections officers are often few in number.

“We’ve worked with the South Carolina Department of Corrections to make sure no contraband comes over the fences of some of the corrections facilities,” says Richland County Sheriff Leon Lott. “In the past, they’ve had a problem in which everything from phones, drugs, and a variety of weapons have been thrown from the outside over the fences and into the prison yards to waiting inmates.”

Lott adds, “With our drone surveillance capabilities, we not only see this, but we are then able to track the perpetrators after the act, and ultimately bring them to justice.”

ROBOTS

Drones aren’t the only remotely piloted platforms in the RCSD inventory. Sheriff Lott’s force of some 700 uniformed officers is also supported by three ground-based robots which, like the unmanned drones, are capable of various tactical and surveillance operations.

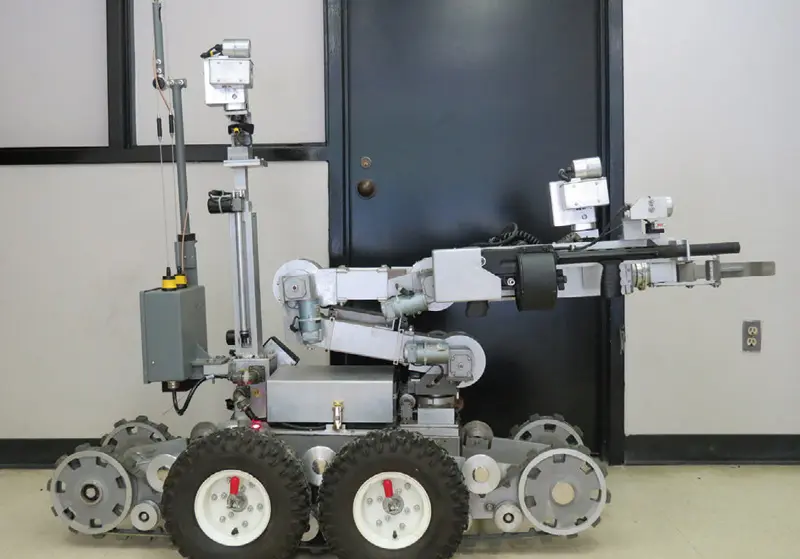

The RCSD’s robots come in three sizes and increasing capabilities: the small iRobot 110 FirstLook (about the size of a remote-controlled toy car and weighing less than ten pounds), the medium iRobot 510 PackBot (a tracked platform weighing less than 100 pounds), and the large Remotec F6-A (a 300-pound force multiplier with a retractable arm and small tires).

shotgun capable of firing less-lethal ammunition.

The small robot, like its bigger brothers, is capable of surveillance and observation. “And we can use the small robot as a non-threatening way to communicate with a barricaded suspect,” says Lieutenant David Linfert, the RCSD’s bomb squad commander. The iRobot 110 FirstLook is used primarily for SRT purposes.

Unlike drones, robots aren’t cheap. The cost of the iRobot 110 FirstLook is approximately $23,000.

“The medium-sized tracked robot can do the same things as the smaller one,” says Linfert, “but is also used for explosive ordnance disposal work and disarming or disposing of IEDs.”

The medium-sized iRobot 510 PackBot, which is capable of climbing stairs and over obstacles, carrying items, and being fitted with multiple cameras, costs around $100,000.

The largest is the Remotec F6A. At a cost of $210,000, the F6A does it all: everything from door and window breaching to vehicle disablement and even serving as an “extra man” for an SRT entry team, in that it can secure a previously searched area so no one can sneak up behind the team.

“With the big robot, we have many capabilities, including the ability to mount weapons,” says Linfert. “We can mount everything from a 37mm tear-gas launcher to a pepper-spray dispersal system to a 12-gauge shotgun that can fire non-lethal ordnance like beanbags and rubber bullets.”

Additional features include radiation, biological, chemical, and explosive monitors utilized in a WMD threat environment. All three robots operate on a wireless radio frequency, can operate up to four to six hours on batteries, and can work in hazardous WMD environs.

BOMB CALLS

Like drones, robots are important pieces in the RCSD inventory, especially in 2017 and even more so in Richland County. According to Linfert, the RCSD receives between 100 and 150 EOD-related calls per year, and they are not all bomb threats phoned in by teenage boys.

Richland County encompasses large-acreage military installations like Fort Jackson and McEntire Joint National Guard Base, vast military reservations that extended much farther beyond their present borders in earlier decades (especially before and during World War II). Land once utilized as munitions impact areas for grenade and mortar training, as well as for artillery live-fire training and aerial bombing runs, has become civilian commercial and residential properties, with housing subdivisions built on land sometimes still concealing unexploded ordnance.

That’s where the robots come in, and the unexpected and unexploded ordnance can be safely defused and disposed of without posing a risk to the lives of RCSD bomb squad officers.

Speaking of which, the RCSD bomb squad directs robot operations, providing support to the SRT and other RCSD elements. The bomb squad is composed of five bomb experts, including full-time members of the SRT, patrol officers, and one bomb technician (Linfert) who is also the bomb squad commander.

The bomb squad and robots also support the local military bases when the military’s own EOD experts are deployed or otherwise unavailable.

Asked about the 100 to 150 “bomb calls” a year, Linfert says they do indeed include juvenile hoaxes but more often than not are newly discovered unexploded wartime munitions.

There are also responses to “fake devices” used to divert officers away from other criminal enterprises, and responses to chemicals discovered in drug labs that can also be used to manufacture homemade explosives.

“Like our drones, our robots are key in mitigating the risk to human life,” says Sheriff Lott.

Linfert agrees, adding, “The robots keep our personnel out of direct danger. They are quickly and easily deployable, and operator friendly.”

For deputies and other law-enforcement officers, especially those operating in the world of SWAT, like the RCSD’s SRT, drones and robots give the good guys an edge in terms of mission success.

In current threat environments, where bad guys also often have access to sophisticated weaponry and high-speed technologies, drones and robots serve as the eyes and ears, and sometimes the arms and hands, of law-enforcement officers. This dynamic is not only key to winning the fight. It’s also critical to saving lives.