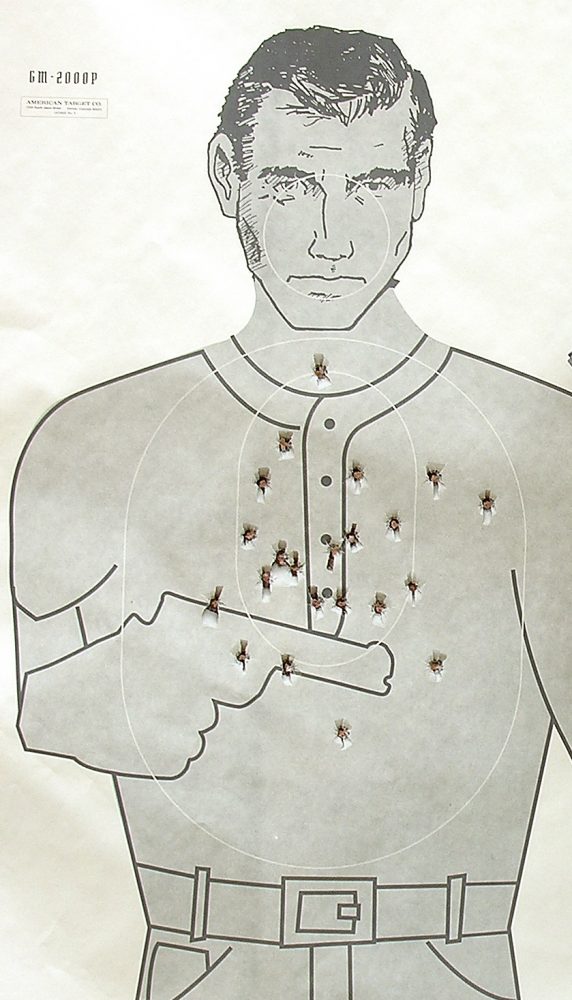

Author intently focuses on target, not sights.

The debate over sighted fire versus point fire has raged on since sights were fashioned on pistols—and I suppose it always will. Both sides are right, in context.

If one finds himself in a situation in which he has time to use the sights, then, by all means, use the sights.

However, if the conflict begins at less than ten feet, in the dark, and very rapidly, as it is statistically likely to, point firing is the way to survive. Under that level of stress, forced to fire very quickly, not only will using the sights slow you down and be almost impossible, but many believe that point firing will be instinctive.

Table of Contents

FLIGHT OR FIGHT

To understand why, we have only to gain some insight into what physiological changes within the body and the mind occur during high stress confrontations. These effects are often referred to as the “fight or flight syndrome,” and are hard-wired into the brain and nervous system. Breathing and heartbeat become very rapid as adrenalin starts to flow. The body begins to divert blood flow from the brain to the extremities. The mind and senses become heightened, but with a strong tendency toward tunnel vision.

Most of these effects are beneficial to fighting empty handed. The adrenalin dump and increased blood and oxygen to the body, notably the extremities, allow us to fight or flee with greater strength and speed; the tunnel vision enables great focus on the threat.

Tunnel vision experienced by people under such stress is so pronounced that it sometimes causes tachypsychia, which is a state of hyper-perception that people liken to seeing the action unfold in slow motion. Some have reported seeing bullets traveling through the air. Many also experience audio-exclusion.

Some of these effects work against us in the modern world, where we arm ourselves with firearms. Burning with adrenalin, heart pounding, and chest heaving, achieving the basic principles of sight alignment, grip, stance, breath and trigger control suddenly becomes a struggle. Though one of the most important principles of marksmanship is to focus on the front sight, and not our target, the brain’s instinctive drive is to look at, and focus on, the threat. Add to this the fact that since the body is directing blood flow from the brain, the boost goes from that of fine motor skills (shooting) to gross motor skills (fighting or running). Less blood and oxygen to the brain means it becomes all but impossible to “think on your feet,” so to speak. That brings us to another characteristic: under stress, we perform as we have trained to perform.

What this means is that we need to train often. To beat the flight/fight syndrome takes thousands and thousands of repetitions of the learned psycho-motor skills that we need to make quick, accurate shots and survive.

Many people who have been involved in firefights report having resorted to point firing, giving no thought to what they were doing. I have noted that while shooting IDPA matches, and shooting scenarios with the police video simulator, I have subconsciously taken to point firing before I was even aware that I was doing so. You may be saying to yourself that these situations cannot possibly approximate the experience of a true gun battle—but that is the point. Even with the moderate stress induced by simulation or competition, the tendency toward point firing emerges.

If there is time to raise the gun and fire, there is probably time to look at the sights, but the plain fact of the matter is that our primal instincts are driven toward more gross motor skills, and toward focusing intensely on the threat—not the sight at the end of the barrel.

At ranges of 15 yards or less, point firing is more natural and faster, and can be effective. One-handed shooting is quicker, not to mention the likelihood that you might find yourself carrying an object in your other hand, or grasping onto something, shoving someone out of the line of fire, or using the free hand to engage your adversary, grab, block, or parry his strike or gun. We must also consider the possibility that one arm or hand may become disabled in a fight for life.

TECHNIQUE

If you think I’ve made the case for point firing (and even if you don’t), let’s move on to basic technique.

Think about pointing with your finger. You’ve done it all of your life; as a baby, it was often your only form of communication. Pointing is natural. Now all we have to do is enhance that natural ability to point with a handgun. You can practice these techniques without even going to the range (though live fire is also a must). The advent of air-soft guns makes this possible, inexpensive, and so many 1:1 copies of actual pistols are made, you are likely to be able to accurately duplicate your actual carry gun.

Popularity of airsoft almost guarantees that you can find an accurate replica of your weapon in terms of dimensions and grip.

KEEP BOTH EYES OPEN

The basics of point firing are very simple: Face your target squarely and look right at it with both eyes open. Raise the gun with your elbow locked until it is eye-level and fire; an alternate technique is to thrust the gun out toward the target until it comes to eye level, and fire. The Isosceles stance should be used, and you should crouch as you engage your target. Real life shoot-outs have shown that under stress, we instinctively crouch and assume the Isosceles stance, so learning to shoot with these natural tendencies gives us less to overcome.

Whether to “swing” the arm up or thrust it forward depends on what is more accurate for you; I find that I usually hit high swinging the arm, and am more accurate “punching” the pistol forward. Picking up the front sight as the pistol moves forward seems to become a subconscious trend.

Buy an airsoft pistol that matches your carry gun. They can be had cheaply on the Internet. The immense popularity of airsoft shooting sports has created a huge market for the guns worldwide, and the result is a wide range of very accurately molded copies of the actual guns.

Staple paper plates or tack pie pans up in your back yard and begin practicing. Start at about six feet and gradually move out to 15 yards. Keep practicing until you are consistently accurate and then go to the range and continue to train with live-fire. You will be amazed at how accurate you become. It really is that simple. Old West gunfighter James Butler “Wild Bill” Hickock knew the simplicity of this technique well when he wrote: “I raised my hand to eye-level, like pointing a finger, and fired.”

The Weaver Stance, two-handed grip, sight-alignment, sight picture and all of the other basics of modern pistol technique provide the most stable shooting platform, best recoil control and most accurate fire. However, for many, they are slower, require more fine motor skills than point firing, go against your natural instincts, and a great deal of training is required to overcome these instincts. Your inclination is to tunnel in on your target, not the sights, and even animals crouch in response to threats. Use a system that utilizes your innate impulses to your advantage, not opposes them.

I once attended the Countermeasures Tactical Institute’s excellent basic SWAT operator’s school, created and taught by Doug Petchtal. One thing that Doug tried to convince us of is that, while the Weaver stance is a very good, solid base to shoot accurately and control recoil, it goes against the natural tendency toward the Isosceles and makes movement forward or back awkward. One of the things that Petchtal does is to video tape each class during each simulation exercise. Simunition ups the adrenalin and motivates one to use the best tactics.

Afterward, the tapes are reviewed, and a common phenomenon comes up time and again: we see students assuming either the Isosceles or an awkward hybrid of the Weaver and the Isosceles. Those with many years of extensive training are able to maintain their Weaver-type stances under stress, but those who do are in the minority.

Are we then to throw out modern technique, discard our sights and train to shoot only from 15 yards and closer? No. But train well in both disciplines. At ranges of 15 yards or more, you should use modern technique and sights. If things go bad quickly and up close, you will be confident and skilled in point-firing; if you are trained well enough to overcome natural proclivities and can get off fast, sighted shots, great. Either way, you win.

SHOOT ONE-HANDED

I recommend doing at least half of your shooting one-handed, even with sighted fire. My reasoning is simple: it leaves one hand free, and anything you can do well with one hand, you can easily do better with both. Try practicing with one hand regularly for six months, then go to the range and try shooting with both again. You will see your shooting improve, yet won’t feel disadvantaged with one hand. You should be able to fire with your weak hand, if necessary, and the reasons should be obvious, though that is the subject of an entirely separate discussion.

MORE THOUGHTS ON TRAINING

I further recommend frequent dry-firing with your weapons, both in aimed and point firing. Dry firing is a highly underrated training tool and will sharpen your skills tremendously. Imagery is a technique that also has its place in your training and everyday life. Succinctly, the subconscious mind does not know the difference between real and imagined. Envision every dynamic of a scenario that you can, and how you think best to handle them. You won’t have the time or ability to think them through under the stress of a lethal threat. Be aware of your surroundings and available cover and concealment as you approach any situation. This will keep you from dying feet away from cover that could have saved you. Learn to prioritize targets according to the level of threat that they pose. Closer targets and targets with more lethal arms are priorities: a man armed with a shotgun should be given attention before his partner with a knife.

Additionally, any time you mentally rehearse a tactical or shooting situation, picture yourself using proper tactics and coming out on top. Train yourself to survive.

Practice rapidly presenting your pistol from concealment if that’s how you are going to carry. All the accuracy in the world won’t help you if you can’t get your weapon out of the holster and into action quickly enough. Train realistically. Don’t take shortcuts that you won’t have available to you in the real world.

FREQUENCY OVER DURATION

Relegate your training to frequent, short sessions. Treat every shot as critical and make each as perfect as possible. If you take on marathon sessions, the human tendency is to “pace” yourself and put more effort into quantity, and therefore quality suffers. Squeezing off 1,000 dry-fire shots a day is worthless if the duration of the session causes you to resort to getting sloppy in your technique. I dry fire almost daily; however, I keep it short. I usually dry-fire three point-fired shots, three “flash-sighted” shots and three precise shots. I also try to fire several shots with my airsoft each week. All of this supplements my live-fire.

If you are a less experienced shooter, you may require more than this at first. Even so, remember– frequency over duration. If you fire 200 rounds in a week, do about 30 per day, not 100 shots on two separate days.

Get an airsoft, practice, and give point firing a try. You’ll be surprised at the accuracy you will develop. Stay with it and you’ll find that you automatically begin to pick up the front sight as you point the pistol and, at the very least, you learn to silhouette the gun as you point. This is a bit slower than strictly point firing, but faster than sighted fire.

Instinct will decide what you have time for if the day ever comes that “practice” is over.

SUGGESTED READING:

Bullseyes Don’t Shoot Back by Col. Rex Applegate and Michael Janich, Paladin Press

Kill or Get Killed by Col. Rex Applegate, Paladin Press

Shooting to Live by William A. Fairbairn and Captain Eric Anthony, Paladin Press